|

| Usain Bolt after capturing 100m gold in Moscow |

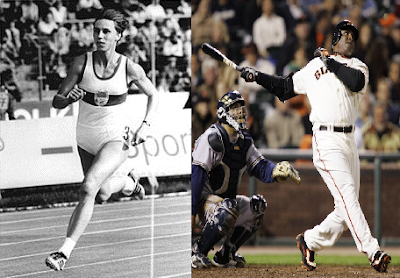

The IAAF World Championships concluded on Sunday with Usain Bolt claiming his third gold medal of the championships, leading his Jamaican 4x100m relay to victory. Bolt now has the impressive haul of 6 Olympic gold medals, 8 World Championship golds, and 2 World Championship silvers. Since his rise to stardom in 2008, Bolt's only championship blemish is his false start in the Daegu 100m final in 2011 (his two silvers were from 2007).

|

| Another GOAT |

Bolt is, with little debate, the GOAT (Greatest Of All Time) of sprinting. Sports fans are quick to anoint athletes as the GOAT, but usually there is some room for debate--there's a short list of athletes whom the general public will not say anything about if they are claimed to be the GOAT. Off the top of my head, Michael Phelps is the GOAT of swimming and Mariano Rivera is the GOAT of closers. Beyond that, things get a little dicey: Jordan or Russell? Was Lemieux more talented than Gretzky? Don't even get started on the greatest hitter of all time.

So now we're talking about a GOAT on a doping blog. This is not good news. What I am going to attempt to do is make a case for why Bolt is

not doping. I am not saying that he isn't, but I'm going to try give some reasons why he might be natural. Despite these reasons, I'll say that I won't be surprised if he were to get busted, and that there is nothing that would be more catastrophic for track and field right now than a positive drug test for Usain Bolt.

Let's start with the sheer absurdity that is Bolt's athletic career. He has run 9.58 for 100m and 19.19 for 200m, both of which are world records. The 19.19 was run as his 8th race of the Championships. A fresh Bolt, at that time, could scare the 19 second barrier, which is more than I can wrap my mind around.

|

| Ben Johnson: the first man under 9.80 |

Here's the list of athletes who have run under 9.80s for 100m:

Usain Bolt

Tyson Gay

Yohan Blake

Asafa Powell

Nesta Carter

Justin Gatlin

Maurice Greene

Ben Johnson

Here's the list of athletes who have run under 9.80s for 100m who have not been associated with the use of PEDs:

Usain Bolt

Oops. In fact, you have to go down to 9.84 before you find someone other than Bolt on the

all-time list who hasn't been immediately associated with drugs. So if we say that the "clean" non-Bolt WR is 9.84, we're thus saying that Bolt is naturally 0.26s faster than anyone in history. That's nearly a 3% difference in performance (for reference, a 10s 100 decided by 0.01s is a 0.1% difference). Hardly adds up, right?

|

| Tyson Gay on his way to 19.58. One of the coolest track pictures I've seen. |

Now let's look at the absurdity of the 200m. On Saturday, Bolt ran 19.66 to win gold. At first glance, that performance did nothing for me. Then I remembered that, until recently, anything under 19.60 was hallowed ground. Five men--Bolt, Yohan Blake, Michael Johnson, Walter Dix, and Tyson Gay--have broken 19.60. So, in reality, this 19.66 is in itself a fairly spectacular performance, but the point I'm trying to get at is that Bolt's excellence has led us to expect times in the 19.3s or faster and anything slower is a poor day. But, if anyone else, save Blake and his freakish 19.26, were to run that fast, he'd gather some attention.

We've now established that Bolt is an extreme outlier and that people who are even remotely close to him doped to do so. Let's defend Bolt a bit.

Bolt has been a sensation in the track world long before he burst onto the scene in 2008 with his 9.72 WR in New York. For example, here's his 200m progression since 2001:

There's nothing too fishy about that other than the drop from 21.73 to 20.58 between 2001 and 2002, but when you realize that he was 14 in 2001 and 15 in 2002, it makes a little more sense (

i.e., puberty happened). In 2004 as a 17 year old he ran a still standing world junior record at 19.93. The kid was a star from the moment he stepped on a track. As a WJR holder, it would follow that maybe someday he would approach the WR. My point is, he didn't pull a Rashid Ramzi going from a 3:39 guy to 3:30 in one year at age 24.

|

| Athletic freak |

Bolt is also a straight up freak (kind of like how

Michael Phelps is a freak, although obviously Bolt's characteristics are different). There is no other way to describe him physically. He stands 6'5" and weighs a slender 207 pounds. There's not much on his frame that doesn't need to be there, which means he doesn't have to expend extra energy carrying that stuff around (dear distance runners reading this: eat. Bolt could put on 20 pounds of muscle in a month but he doesn't need to; that is a whole different league than trying to take off 5 pounds from a 100 pound frame by starving yourself). His 6'5" stature means his steps are ridiculously long. The Guardian reported that he took

41 steps in the London 100m final while the average elite 100m runner takes 44. But, speed is a combination of stride length and turnover (how quickly the legs cycle through between steps). Traditionally, taller athletes have slower turnover because it takes longer for their long legs to cycle through. Bolt, on the other hand, has the turnover of a 5'10" guy. As such, he has a lethal combination of stride length and turnover that makes him the best ever.

Much has been said about the poor quality of Bolt's start. While his start is certainly not perfect, let's take a moment to dispel the myth that he has a terrible first 30m of his 100m. The WR for the 60m is 6.39 held by Maurice Greene. When Bolt ran 9.58 in 2009, the first

60m of that race was timed at 6.31 (w=+0.9). Even more frightening is that in his 9.69 run in 2008, he had his first 60m timed at 6.32 with

no wind (w=±0). So, he's covering 60m faster than Maurice Greene, who is of a traditional short-sprinter build (5'9.5", 170lbs).

|

| En route to 9.69 and his first Olympic gold |

Bolt also has the best technique I've ever seen. I remember my jaw being on the floor the first time I saw him run--and it wasn't because he was running 9.69 celebrating for 30m. The whole reason why he's such a clown before races isn't for the attention; he does it to keep his body relaxed. This optimizes his stride length and allows him to conserve energy. Without going into the finer details of technique that only I will enjoy reading, the positioning of all parts of his body is worlds better than anyone else. Sprinters of all ages should spend hours watching his race videos and looking at pictures of him at various phases of his races. Even having half the technique that Bolt does would improve an athlete's speed tremendously.

(Post-publication clarification: I should note that Bolt's form isn't perfect. There are certain areas where he could improve, most notably, how he runs the turn in the 200. His top-end technique, though, is out of this world.)

So there you have it. Bolt has been an age-group superstar turned senior-level megastar who won the genetic lottery and was born with incredible natural technique. He's a borderline once-in-a-lifetime athlete. And let's hope he's done it cleanly.